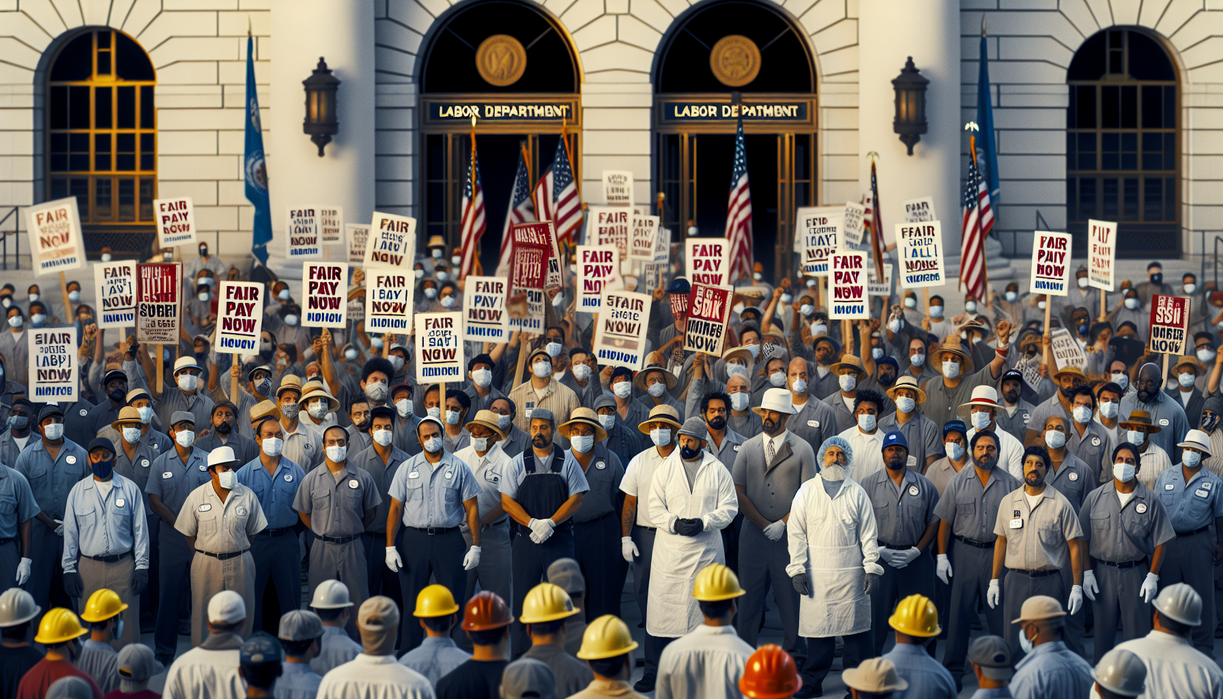

gotyourbackarkansas.org – The growing department of labor investigation into claims of underpayment at downtown state offices is shining a harsh spotlight on how essential workers are treated behind polished government walls. Contract janitors say a company hired to keep those buildings spotless has instead wiped away basic labor protections. Their protests, unfolding right outside the very institutions meant to protect workers, reveal a troubling disconnect between law on paper and life on the night shift.

At the center of the department of labor investigation is CVVY Enterprises, a cleaning contractor accused of paying below minimum wage and dismissing staff without fair cause. Janitors allege that short paychecks, sudden schedule cuts, and abrupt firings have become routine. Their struggle raises a larger question: if workers at state offices struggle to claim legal wages, what does that mean for others with even less visibility and leverage?

Why a Department of Labor Investigation Matters

A department of labor investigation is not just bureaucratic paperwork; it is one of the few formal tools low-wage workers can use to challenge exploitation. When janitors come forward, they risk retaliation, lost hours, or outright dismissal. That risk explains why such complaints often surface only after conditions become unbearable. These janitors are not only cleaning offices; they are also cleaning up a broken slice of the labor system.

At first glance, the accusations seem straightforward: alleged pay below the legal minimum, unpaid tasks before and after shifts, and termination when workers speak up. Yet each element reflects a deeper pattern. Underpayment suggests either misclassification, off‑the‑clock work, or wage theft. Abrupt firings hint at an effort to silence dissent. Together, they form a picture of power imbalance, where one side controls the schedule, the paycheck, and sometimes even immigration-related fears.

This department of labor investigation also carries symbolic weight because it involves state offices that should embody compliance with labor standards. When cleaning staff assigned to public buildings claim routine violations, it undermines confidence in public procurement. Taxpayer money is supposed to support lawful, ethical contracts. Instead, workers say it funds a race to the bottom, with the cheapest bidder winning contracts at the expense of basic human dignity.

Inside the Janitors’ Allegations

According to workers protesting outside the buildings they clean, the trouble begins with wages that fail to reach the legal minimum once hours and tasks are tallied. Some janitors describe being asked to arrive early to prepare supplies or stay late to finish extra floors, with no additional compensation. If true, this off‑the‑clock labor effectively lowers hourly pay below official rates, a classic red flag during any department of labor investigation.

Janitors also report abrupt changes to schedules after they raise concerns. One day, they have a full slate of hours; the next, their schedule is cut in half or eliminated. For workers living paycheck to paycheck, even a small reduction can mean unpaid bills or eviction. The allegation is that such cuts are not random, but aimed at those who dare to question payroll discrepancies. That pattern, if documented, creates a strong narrative of retaliation.

Then there are the firings: workers claim they are dismissed without clear explanation, sometimes right after speaking with coworkers about wage problems. From a legal standpoint, an employer may attempt to frame these separations as performance-based or due to restructuring. The department of labor investigation will need to examine records, emails, and witness statements to determine whether those reasons hold up or conceal an attempt to silence employees organizing for fairness.

How This Case Reflects a National Problem

Although this department of labor investigation centers on one contractor, the story echoes across cleaning crews nationwide. Outsourcing has allowed public agencies and private companies to distance themselves from direct employment responsibilities, while still benefiting from low-cost labor. Contractors compete by trimming payroll, often at the expense of compliance with wage laws. Janitors, security guards, and cafeteria workers feel the squeeze first. My perspective is that focusing solely on individual bad actors misses the structural incentive: when contracts reward the lowest bid without robust oversight and enforcement, exploitation becomes a predictable outcome rather than an unfortunate accident. Real change will require not only punishing violations, but redesigning how public work is contracted, monitored, and valued so that clean floors never come at the cost of dirty labor practices.

Public Contracts, Private Pressure

One of the most troubling aspects of this department of labor investigation is the setting: state-run offices that rely on taxpayer-funded contracts. In theory, such contracts should set a high bar for worker treatment. In practice, many agencies focus on budgets first, worker conditions second. When cost becomes the main criterion, contractors face enormous pressure to minimize labor expenses. That pressure can lead to understaffed crews, forced speedups, and wages that barely scrape legal standards.

CVVY Enterprises, at the core of the allegations, is not unique in pursuing public work. Contracting for state facilities is often seen as a stable revenue stream. Yet stability for the company does not always translate into stability for the workforce. Janitors may endure constant schedule shifts, last-minute location changes, or overnight rotations. Any hint of complaint can be framed as a “bad attitude,” giving cover for removal. The department of labor investigation will likely examine whether such patterns were isolated incidents or systemic practice.

My own reading of similar cases suggests that many violations begin with small shortcuts that gradually become standard operating procedure. Perhaps overtime is missed once, then twice, then turns into a habit. Perhaps a manager threatens to cut hours if a worker calls a hotline. Over time, these individual actions harden into an informal policy. A strong department of labor investigation can break that pattern, but only if it leads to real consequences: back pay, penalties, binding compliance plans, and, where necessary, loss of eligibility for future public contracts.

The Human Cost Behind the Paychecks

Amid legal details about wage rates and termination procedures, it is easy to forget the human beings at the center of this department of labor investigation. Janitors often work nights, when most of the city sleeps. Many juggle more than one job or care responsibilities at home. When pay comes up short even slightly, the shockwave hits food budgets, medication purchases, childcare, or remittances sent to family abroad. A missing hour on a timesheet is not a clerical error; it is a skipped meal or a late rent payment.

The psychological stress is just as severe. Workers who suspect underpayment often fear speaking up. They might worry about being branded troublemakers, or about immigration questions suddenly surfacing. That fear builds into a constant low-level anxiety: will today be the day my badge stops working, my schedule disappears, or a supervisor tells me I am no longer needed? Such stress affects sleep, health, and relationships, long before any official complaint begins a department of labor investigation.

From my perspective, labor rights conversations tend to focus on high-profile industries, while janitors remain invisible unless something goes wrong. Yet they are the ones disinfecting restrooms, clearing trash, and keeping public spaces safe from health hazards. When they are underpaid or intimidated, the message is clear: the comfort of office workers matters more than the security of those who clean up after them. A fair outcome to this department of labor investigation would send the opposite message, affirming that basic dignity is non-negotiable, no matter how humble the job title.

A Reflective Conclusion

This department of labor investigation may result in back pay, penalties, or revised contracts, but its deeper legacy will depend on what we learn from it. If the story ends with a settlement, then quietly fades, the underlying incentives to cut corners will survive. If, instead, public agencies toughen contract standards, demand transparent payroll audits, and give workers safe avenues to report abuse, this moment could mark a subtle but real shift. My hope is that the courage of janitors who stepped forward becomes a turning point, where we value not only shiny floors and tidy offices, but also the rights of the people who make those spaces usable. Justice at work should not require a protest outside the very buildings meant to protect it.